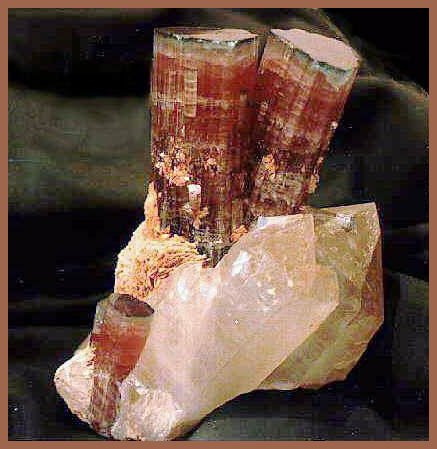

Tourmaline is a mineral that is complex in nature. Due to this complexity, it exhibits more range of color than any other mineral or gem (its closest competitor is corundum [sapphire/ruby]). A silicate mineral of reasonable hardness (approx. 7-7 1/2), the crystal form is hexagonal, but is most often seen as crystals of bulging triangular cross-section, with striations running the length of the crystals. If the crystals are doubly-terminated, usually one end will exhibit a predominately flat or basal termination, the other with a point (pedion termination faces). The crystals can grow stubby, but most often are elongated or pencil shaped.

The most commonly seen tourmaline is the sodium-rich black variety known as "schorl". It forms in simple to complex granitic pegmatites. Iron is the primary coloring agent in this material. If the pegmatite contained lithium, manganese, and other rare elements, the colored varieties of tourmaline known as "elbaite" could form. Many elements can freely substitute for others in the tourmaline family. Elbaites often form beautiful crystals in colors of pink, red, green, blue, orange, yellow, or other shades, even colorless.

The different colors have sometimes been given identifying names of their own: "indicolite for blue, "rubellite" for red, "achroite" for colorless, and sometimes the green is referred to as "verdelite". Authorities occasionally get into a dispute over what actual color tones comprise these varieties. For example, rubellite originally meant bright red, like a ruby. Eventually pink tones were referred as rubellite often enough that it became acceptable to some authorities but not to others. Often colors shade from one hue to another, sometimes blending, sometimes remaining distinct. The color zoning can form both concentrically and longitudinal. The most common are those having a pink or red core and a green skin. They were nicknamed "watermelon" tourmaline because of the resemblance of the cross-sections to a slice of watermelon fruit. Sometimes crystals that started growing as schorl finished growing as elbaite, especially in pocket zones. These clay-filled bubbles in the granite formed when the rock was cooling, and contained the space necessary for gem crystals to form. If no pockets were present, the mineral is usually cracked and included ("frozen" into the quartz, feldspar, or mica) and most often not suitable for gemstones. The pocket material, on the other hand, is frequently transparent, and sometimes "flawless". The pockets can also contain other exciting crystals and gems in addition to the tourmalines. As a matter of fact, gem pockets don't have to include tourmalines at all. Other gems found there can be beryls (aquamarines, heliodors, or most often morganites), topazes, apatites, smoky quartzes, lepidolite mica, spodumenes (kunzite, triphane, hiddenite), and rare minerals such as herderite or beryllonite. An interesting aspect of the crystallization sequence in pockets mean that sometimes crystals, although not uncommon in themselves, rarely form in combinations. For example, aquamarines and heliodors (golden beryl) are rarely (if ever) found with elbaite tourmaline, but the pink or peach variety, morganite, is frequently associated. This is because too much iron present forms schorl, not elbaite, yet iron is the primary coloring agent in aquamarine and heliodor. Another example would be rose quartz, which although fairly common in pegmatite's, is rarely found in direct combination with tourmaline or beryls for some reason.

Crystals of schorl or elbaite can occasionally reach three foot long or more, although the average is much smaller. One very rare type of elbaite which has formed turquoise to electric blues in color, is due to inclusions of copper ions. It has so far only been found in a couple of mines in the state of Paraiba, Brazil, and is known in the trade as Paraiba tourmaline. Prices per carat can reach an astounding five figures. More recently, copper-bearing elbaites have been found in one spot in Nigeria, and many of the Mozambique dikes. A debate ensued after their discovery as to whether they could be properly referred to as "Paraiba", since it was actually named after a physical locality in Brazil. Last I heard the authorities had agreed upon allowing the terms "paraiba-like", or "copper-bearing" to be used.

More recently, some sellers have referred to a fairly abundant similar tinted light to medium dark blue/green material from Afghanistan as Paraiba, or Paraiba-like, but this material apparently contains no copper. Only the colors are similar.

Other types of tourmalines include "liddicoatite", a rare multicolored gem variety so far found in Madagascar and Siberia. It resembles watermelon elbaite in most respects, but cross-sections typically show triangular zoning, often in numerous colors and shades. Also included are "dravite" and "uvite.". These are calcium-rich varieties found mostly in metamorphic rocks like marbles. Dravite is usually brown or black, but sometimes can form a yellow to green material that can be used as gems. Uvite is usually black, but can be other colors as well. It is seldom found in gemmy crystals. Buergerite is a bronzy-brown color variety found in rhyolite in Mexico and has not been found in gem quality. The chemical composition is similar to schorl. A recently discovered variety, "foitite" (Gems and Gemology, Spring 1994), is also similar to schorl but lacks the sodium ions. Only a few non-gem bluish-black crystals were discovered and came from southern California. It has apparently shown up a few other places since then.

New tourmaline family members seem to be discovered every year or two. I do not have the space and time to list them all, but this information is available in some of the newer publications on the subject.

An elbaitic tourmaline rich in the element bismuth has been discovered in Zambia (often reported to be from Mozambique). These are gem quality pink/green/black nodules, but so far there has been no attempt to declare these another variety.

One of the most exciting aspects of tourmaline is that it frequently forms spectacular and beautiful crystals, which pleases the mineral collector, as well as provides beautiful gemstones. Occasionally this creates a conflict: Do you sacrifice a rare crystal, beautiful in it's own right, to make a potentially even more valuable gemstone? My personal feeling is that there are plenty of damaged, chipped, broken or water-worn crystals and crystal sections to cut without sacrificing perfect crystals of great beauty or rarity. I realize there can be exceptions to this rule, but I think it's a good principle to live by.

What about tourmaline as a gem? Well, it's reasonably hard, has a moderate refractive index which give the cut stones warmth, and it comes in many colors. There is no cleavage to speak of, although crystals are often stressed perpendicular to the length, which can make cutting an adventure. The stress can cause what looks like a perfectly solid piece to fall apart suddenly into two or more pieces while cutting. If the colors are grayish and unsaturated or unpleasant, the stones are very inexpensive.

If the colors are saturated and bright, they are very desirable and can get rather pricey. The most desirable colors include "Paraiba" blue; indicolite; teal; flawless watermelons or bicolors; rubellite; pink, especially "hot" pinks; chrome greens; and minty to medium bright greens. Like emeralds, moderate inclusions in some of the colors are considered acceptable, most notably hot pinks. Most saturated bicolors are flawed also. Retail prices usually run from about $40 per carat to about $500 per carat, depending on color, clarity, and size, but can sometimes go considerably higher. Because of the crystal shapes they are found in, cut stones are often emerald cuts or the more elegant cushion cuts (especially the blues and greens). There are enough odd-shaped pieces found to supply most of the most common shapes however, such as rounds, pears, and ovals. The best color in pinks and rubellites is down the c-axis (unlike blues and greens) so they are maybe less often cut into emerald cuts. Because of strong dichroism in the crystals, the color tones down the c-axis of many greens and blues are too olive, too dark (even black). The ends must be cut very steep on the pavilion to keep out this dark color. Round stones cut with this strong dichroism in them exhibit the famous "bowtie effect". This is sort of like an iron cross in shape, with one direction showing good color and the other direction showing poor color or no color at all. Like many gemstones on today's market, colors in tourmalines can sometimes be improved by heating or irradiating. Light pinks can go to rubellite red with irradiating, whereas dark stones of any color can sometimes be lightened to a more satisfactory saturation with heat. Heating does not always work for some reason though, and you always risk cracking the stones with this method. One thing is that man has never been able to produce true synthetic tourmaline, so you can be assured they are natural in that respect.

Some of the many places good gem tourmaline has come from: the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil (all colors) is still the largest producer today. If you ever get a chance to read about the huge find of enormous cranberry rubellites at the Jonas Mine near Itatiaia, do so. It's a very fascinating story; Afghanistan (beautiful greens and blues, some pinks). These continue to be available in some quantity, mostly through Pakistani dealers, despite the war-torn nature of the source; Pakistan itself seems to be experiencing a rising production; Nigeria (large gem reds and pinks, greens); Madagascar, Mozambique, Zambia and many of the southern African countries (all colors); Namibia has produced some beautiful blues, teals, and a few reds in recent years, and a great deal of facet grade material from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, much in pale or pastel tones; Tanzania has produced gem dravite: "pumpkin" orange, light green, yellow, and true chrome green, along with minor amounts of elbaite; Russia (Siberia), Viet Nam, India, and Sri Lanka have produced minor amounts of gem and specimen material. Many of these localities have been written up at one time or another in GIA's publication, Gems and Gemology. Old copies of Mineralogical Record or Lapidary Journal, to name a couple of other sources, can contain excellent articles on them as well.

In the U.S., the states of Maine and California are famous for tourmalines. In fact, the oldest operating gem mine in the U.S. was opened shortly after a discovery of gem tourmaline crystals entangled in uprooted tree roots around 1812 by the Hamlin brothers. This mine later became the Mt. Mica mine near Paris, Maine. Maine has produced many very fine gem crystals over the years. It is especially noted for particularly fine greens and blues, but some pink and watermelon has been produced. Most of the discoveries have been minor in size, but an enormous pocket of some of the finest watermelon crystals ever discovered was found in the early 1970's at Newry's Plumbago Gem Pit. The company that mined it, Plumbago Mining Co., also reopened the old Mt. Mica Mine, with light success, then sold it to another operating company who has experience continued success. An old mine known as the Berry/Havey Quarry was vigorously and enthusiastically worked in modern times by Stephen Welch with excellent success, and even more recently by others. Recent YouTube videos have shown some remarkable gems under the name of the Sparhawk Mine. The Tamminen Mine, Mt Rubellite, and Mt Marie have produced nice specimens of elbaite. As a side note, some remarkable rare rose quartz crystals were recovered from both Mt Mica, the GE pit, and Plumbago Mt., and a very large orangish specimen of gem morganite were discovered at the Berry Mine within the last few decades . Morganite is not common in the New England pegmatites.

California brought tourmaline to light as early as the turn of the century. Two mines are primarily responsible for its fame: the Stewart Lithia Mine at Pala, and the Himalaya Mine at Mesa Grande. The Stewart is especially famous for its crystals of "bubble-gum" pink tourmalines and good lapidary-grade lepidolite (pink to purple lithium mica). Some small greens of decent hue have been found, as well as bi-colors, grayish-blues, achroite, and a small area of true cherry red rubellite. The Himalaya is famous for burgundy tones, pinks, yellow-greens, flawless bi-colors, and many beautiful crystal specimens.

The Tourmaline Queen Mine at Pala produced a few excellent pockets of large "hot pink", crystals with dark blue "caps", or flat terminations. Not a lot of gem material came from these, but the crystals are among the most beautiful in the world. The nearby Tourmaline King Mine has recently seen a revival of nice crystals being actively mined there.

The Pala Chief and a number of smaller mines on the hill there have produced small amounts of pink and other colors, plus numerous gem beryls (morganite and aquamarine) and gem spodumene (kunzite). More recently the nearby Oceanview Mine was operated successfully for tourmaline and other gems. A concession was opened to the public there as well, where you can screen piles of rock and dirt brought from inside the mine for this purpose. Of the three in operation there pre-covid (the Himalaya and Stewart also had concessions), the Oceanview is the only one still open, as far as I am aware.

The Cryogenie, was operated by Ken and Dana Gochenour in the early 2000's, and produced a few pockets of fine crystals. The Little Three Mine at Ramona has produced dark greens and other tones in small quantities.

Connecticut produced some nice elbaites (along with aquamarines and heliodors) years ago at the Gillette Quarry and Strickland Quarry. They were never abundant, but quite gemmy, attractive, and reached sizes up to 4" or more, usually in elongated crystals. The Gillette Quarry pieces had many rather odd or unusual colors and combinations. These areas are now closed, I believe.

New Hampshire and Massachusetts have produced very minor amounts of elbaite in years past. Some elbaite was discovered in upper Wisconsin, but is small and non-gem, at least what I've seen.

The southeastern U.S. has produced a fair amount of schorl, but little, if any elbaite. I have one specimen that is supposedly from Brushy Creek, No. Carolina that is half schorl and half green gem elbaite. But I can find no one who can verify that it actually came from there. Personally I have some doubts, although I have found mention of a few minor spots for green tourmalines, including Brushy Creek and the mountain on which the Ray Beryl Mine is located.

The Mineral Mountains near Milford, Utah reported a small quantity of rare green tourmalines at the southern end of the range. Little information is available, but appears it may be in a privately owned quarry.

The Black Hills region of South Dakota has a large area containing pegmatites with tourmalines (as well as many other minerals). Unfortunately, pockets are almost non-existent. Scientists speculate that granites that form too shallow or too deep in the earth's crust tend to not allow the formation of gem pockets. But nice specimens of schorl are super abundant here, and several mines produced a considerable quantity of specimen-grade elbaites, and an occasional gem piece. The most remarkable was the Bob Ingersoll Mine, which I believe is now closed due to vandalism and other issues.

Colorado has a mine complex near the Royal Gorge (Canon City) called the Mica Lode/Meyers Quarry that apparently produced considerable gem tourmaline around the turn of the century. From what I have been able to gather, the tourmalines formed in a shear zone of some sort, rather than traditional pockets. This information is however, disputed. Once this zone had been mined through, there were no more gems. Unfortunately, very few specimens from this locality remain that are properly identified, because many resembled gems from the California mining area. If any reader has pictures or more information regarding this area, I would be interested in hearing from you.

Dark green gemmy Tourmaline crystal before cutting. Reported to be from Canon City from the early 1900's.

Dark green gemmy Tourmaline crystal before cutting. Reported to be from Canon City from the early 1900's.

West of Royal Gorge near Texas Creek are several small areas with nice schorl crystals and schorl grading into dark green non-gem elbaite, but most of it is in privately-owned mines. One verbal communication by a geologist claimed there was apparently some gem yellows found one year.

Another pegmatite region near Ohio City (Gunnison County) contains a few mines with elbaite, the most famous of which is the Brown Derby Mine. This is another unpocketed area though, so gems are basically non-existent from here. Material comes in many colors and decent sizes, including considerable watermelon, pink, green, yellow, colorless, blue, and purple, but much has a kind of strange waxy appearance. By far most pieces are completely opaque, occasionally grading into translucent.The bi-colors are particularly attracive, considering their lack of gemminess and transparency. For some reason the yellows and purples tend to be the gemmiest. A few pieces will cut interesting cabs. One interesting feature is that most of the crystals formed in simple hexagonal cross section, as opposed to the more common "bulging triangles" (due to twinning) in most occurances.

There are rumors of other "lost" elbaite areas in the state. However, for as much granite and pegmatite as there is exposed here, tourmaline is surprisingly rare. Schorl is fairly abundant locally in some areas near Crystal Mountain west of Ft. Collins.

I have also heard of sporadic small finds of elbaite in north-central Wyoming, and northern New Mexico, but very little information is available.

***End of My Tourmaline Blog. If you have any comments or questions about this article, you are welcome to email me.***